- European Central Bank publications

29/ Signalling the Governing Council’s monetary policy stance through the deposit facility rate

29 novembre 2024

Post de Gaston Reinesch, Gouverneur de la BCL

Signalling the Governing Council’s monetary policy stance through the deposit facility rate[1]

This post reviews how and why the Eurosystem deposit facility rate (DFR) became the interest rate used to steer the monetary policy stance with a view to maintain price stability.

Structural liquidity deficit prior to the global financial crisis

Prior to the global financial crisis arising in 2007-2008, the euro area banking system as a whole faced an aggregate liquidity deficit, reflecting primarily its need for banknotes and the obligation to fulfil reserve requirements.[2] Back then, the euro area banking system, as a whole, relied on refinancing from the Eurosystem and the bulk of central bank liquidity was provided to the banking system – against adequate collateral – by means of main refinancing operations (MROs). MROs were (and still are) conducted regularly on a weekly basis by the Eurosystem national central banks (NCBs) and have a maturity of one week.[3] While participating credit institutions bade the amount of reserves they wished to obtain, prior to the global financial crisis the total amount of liquidity provided to the banking system as a whole was determined by the Eurosystem. The Eurosystem provided an amount of central bank liquidity allowing euro area banks to meet their liquidity needs in a smooth manner and at a rate consistent with the policy intentions. Euro area banks only held small amounts of excess reserves.

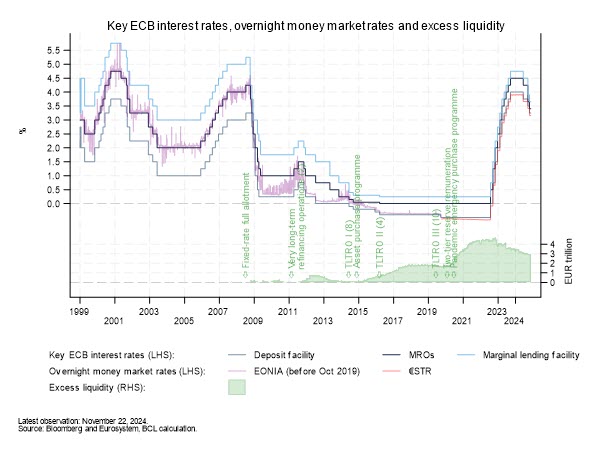

With MROs providing the bulk of central bank liquidity, the interest rate applied to MROs determined the refinancing conditions for credit institutions in the euro area which, in turn, transmitted to the wider financing conditions, the saving, spending and investment decisions of households and firms and, ultimately, the inflation rate. The overnight money market rate, as measured by EONIA[4], therefore followed closely the rate applied to MROs (the purple and navy blue lines in the graph below).[5] The monetary policy instrument of the interest rate on MROs thus represented the key ECB interest rate, crucial for steering short-term money market interest rates, managing the liquidity situation and signalling the stance of the Governing Council’s monetary policy.

In order to limit rate volatility, the Eurosystem also implemented monetary policy and affected short-term interest rates by setting the interest rates on its standing facilities, i.e. the deposit facility and the marginal lending facility. The deposit facility can be used by counterparties to make overnight deposits at a Eurosystem NCB remunerated at an interest rate lower than the MRO rate (i.e. the DFR). The marginal lending facility may be used by eligible counterparties to borrow overnight from a Eurosystem NCB at an interest rate higher than the MRO rate against eligible assets.

In principle, individual credit institutions with a shortage of reserves can also borrow overnight from those with excess reserves at the corresponding interbank rate. As eligible credit institutions can borrow overnight from the Eurosystem at the marginal lending facility rate, in normal times, they have no incentives to borrow in the money market at a higher rate. The rate on the marginal lending facility therefore, in principle, forms a ceiling for the overnight interbank rate. At the same time, since eligible banks can deposit funds at the Eurosystem’s deposit facility rate, in normal times, they are unlikely to lend funds in the interbank market at lower rates. The deposit facility rate therefore, in principle, forms a floor for the overnight interbank money market rate.

Hence, by setting the rates on the standing facilities, the Governing Council effectively determined the corridor within which the overnight interbank rate fluctuated. Between 9 April 1999 and 8 October 2008 the width of the corridor was 200 bps.[6] In general, the deposit and lending rates applied to the Eurosystem’s standing facilities stood well below and well above, respectively, EONIA. From this perspective, the corridor incentivised banks to manage their liquidity via money markets and very limited recourse was made to the Eurosystem’s standing facilities.

From structural liquidity deficit to ample liquidity

The steering of short-term money market rates, the liquidity management and the signalling of the monetary policy stance in the euro area changed substantially during the period of acute financial market tensions arising in 2007-2008. As a result of very elevated uncertainty, perceived counterparty risk and market segmentation, the effective allocation of liquidity between banks in need of liquidity on the one hand and those with excess liquidity on the other hand was jeopardised and money markets became impaired.

Faced with risks to the liquidity situation of solvent banks, the flow of credit to households and businesses and ultimately the smooth and effective transmission of the single monetary policy, in October 2008 the Governing Council decided to conduct MROs through a fixed rate tender procedure with full allotment at the MRO interest rate. Under this procedure, eligible euro area credit institutions bid the amount they wish to transact at the fixed rate, subject to adequate collateral, and the Eurosystem accommodates all bids in full. The total amount of liquidity is no longer determined by the Eurosystem alone and the total amount allotted corresponds to the sum of the bids (backed by collateral) by participating banks.

Owing to high uncertainty and perceived counterparty risk, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, some banks preferred to keep more central bank reserves than required and to deposit the additional reserves in the Eurosystem’s deposit facility instead of lending them to other banks.

Moreover, the Governing Council announced various types of measures aiming to ensure a smooth and efficient monetary policy transmission process and to fulfil the price stability mandate in an environment characterised by persistently low inflation. The combined use of large refinancing operations at very attractive terms and large-scale asset purchases led to a substantial increase in reserves held by the euro area banking system (the green shaded area in the graph above).[7] Factors outside the realm of monetary policy also fuelled the demand for central bank reserves in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, including regulatory measures and changes in bank risk management.

The transition from a structural liquidity deficit of the euro area banking system to an environment of ample aggregate excess liquidity fundamentally changed the relationship between the ECB key interest rates and overnight interbank rates. Rising excess liquidity pushed unsecured overnight rates towards the DFR. With the euro area banking sector on aggregate endowed with surplus funds and, in principle, willing to lend, banks in need of funding are able to borrow at rates not much higher than the DFR. The volume of regular shorter-term main refinancing operations, by contrast, declined substantially. Accordingly, whereas prior to the global financial crisis the EONIA rate closely followed movements in the MRO rate, in the presence of ample excess liquidity overnight money market rates – a key determinant of financing conditions more broadly – tend to follow the DFR (see graph above). The DFR thus became the policy rate used to signal the monetary policy stance in the euro area.

The shift towards an environment characterised by ample excess liquidity went along with substantial changes in the money market itself. Reflecting the banks’ assessment of counterparty risks, changing regulations and liquidity conditions, the volume of unsecured overnight interbank transactions as measured by EONIA declined substantially (the average trading volume dropped from almost EUR 48 billion in 2007 to less than EUR 2.5 billion during the first nine months of 2019) and unsecured interbank trading became increasingly concentrated on a few reporting banks.[8]

Following these developments, EONIA was considered no longer compliant with the EU Benchmark Regulation[9] requiring reference rates to be robust and reliable as of January 2020. In September 2018 the Working group on euro risk-free rates established by the European Commission recommended that the euro short-term rate (€STR) be used as the risk-free rate for the euro area.[10] While EONIA only covered the unsecured overnight interbank money market, the €STR covers the wholesale euro unsecured overnight borrowing costs of euro area banks resulting from trades with banks and non-bank financial counterparties (e.g. money market funds and insurance companies) and entities located outside the euro area, as reported by major euro area banks. By covering also non-bank entities active in the money market, the broader scope of the €STR mitigates issues related to the diminishing role of unsecured interbank lending covered by EONIA.

In addition to transactions conducted by credit institutions that have access to the Eurosystem’s standing facilities, the €STR also includes transactions conducted by entities without such access. While entities with access to the standing facilities in normal times are unwilling to lend at a rate lower than the DFR and to borrow at a rate above the one applied to the marginal lending facility, entities without such access may be willing to do so. In the present environment where credit institutions (on aggregate) have ample excess liquidity and make substantial recourse to the Eurosystem’s deposit facility, for instance, entities without access to the deposit facility may be able to make deposits in the money market at levels below the DFR only. The level of the €STR is therefore not necessarily limited to the range spanned by the interest rates on the Eurosystem’s deposit and marginal lending facilities.

Since the publication of the €STR in October 2019, excess liquidity ranged between approximately EUR 1.7 tn and almost EUR 4.7 tn and the €STR stood below the DFR. While the spread between the €STR and the DFR varies over time, the €STR closely follows the DFR.[11] Changes of the DFR therefore continue to transmit reliably to the overnight wholesale borrowing costs and the wider financing conditions, the saving, spending and investment decisions of households and firms, and, ultimately, the inflation rate.

The Governing Council continues to steer the monetary policy stance through the DFR

Looking through some short-term fluctuations, excess liquidity declined since late 2022 (green shaded area in the graph above). Meanwhile, nine of the ten TLTROs III matured. In line with the discontinuation of reinvestments under the APP as of July 2023[12], the APP portfolio is declining as assets held reach maturity. Moreover, since the second half of 2024 the Eurosystem no longer reinvests all of the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the PEPP, thereby reducing the PEPP portfolio by EUR 7.5 bn per month on average, and the Governing Council intends to discontinue reinvestments under the PEPP at the end of 2024.

While remaining significant over the coming years, excess liquidity in the euro area banking system is therefore expected to gradually decline. Against this background, between December 2022 and March 2024, the Governing Council reviewed the Eurosystem’s operational framework for steering short-term interest rates in the euro area. The Governing Council concluded its review by announcing, among others, that it would continue to steer the monetary policy stance through the DFR.[13]

[1] I would like to thank Patrick Lünnemann for support in preparing this article and welcome any observations and perspectives about the wide-ranging subject matters of this blog post as well as any suggestions for improvement.

[2] In pursuance of its monetary policy objectives the ECB requires credit institutions in the euro area to hold compulsory deposits on accounts with the Eurosystem national central banks (NCBs), typically referred to as “minimum reserves” or “required reserves”. The amount of reserves to be held by a given bank is determined based on elements of its balance sheet.

[3] The Governing Council shortened the maturity of MROs from two weeks to one week as of March 2004.

[4] Until 2019, EONIA was the main reference rate for unsecured European interbank money markets, reflecting the rate at which banks of sound financial standing in the EU and in the European Free Trade Area lent funds in the unsecured overnight interbank money market in euro (i.e. loans granted based on the borrower’s credit worthiness, not backed by any type of collateral, https://www.emmi-benchmarks.eu/benchmarks/eonia/).

[5] During 1999 - 2007, the average spread (in absolute terms) between the MRO rate and EONIA was approximately 10 basis points (median spread: approximately 7 bps). The MRO-EONIA spread used to be much smaller during a maintenance period when credit institutions could smooth out daily liquidity fluctuations (“averaging provision”). The higher average spread owed to spikes in the EONIA towards the end of maintenance periods when the reserve requirement became binding as credit institutions could no longer compensate transitory reserve imbalances by opposite reserve imbalances.

[6] The width of the corridor was 100 bps from 9 October 2008 to 20 January 2009. The spread between the rate on the marginal lending facility and the DFR widened again to 200 bps during 21 January 2009 – 12 May 2009, but narrowed afterwards.

[7] During the sovereign debt crisis peaking 2010 – 2012, for instance, the Governing Council launched so-called very long-term refinancing operations (VLTROs) offering banks longer-term financing (up to three years). Between 2014 and 2019, with a view to incentivise lending to euro area households and businesses and to lift inflation towards its medium-term price stability objective, the Governing Council launched three series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). TLTROs are targeted refinancing operations in that the amount that banks could borrow or the interest rate at which they could borrow were linked to their lending to households (save lending for house purchase) and non-financial corporations. Under TLTROs banks could obtain financing for up to four years (TLTRO II) or – contingent on the lending performance of each bank - temporarily at interest rates below the DFR (TLTRO III). The total amount of lending provided under TLTRO III reached EUR 2.2 tn. Starting late 2014/early 2015, the Governing Council undertook large-scale purchases of various types of assets under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP). In combination with net purchases under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) announced in March 2020, the Eurosystem’s total stock of assets held or monetary policy purposes reached almost EUR 5.0 tn. The introduction of tiered reserve remuneration in October 2019 to mitigate the side effects of negative interest rates lowered the average cost of holding reserves.

[8] In 2017, about 88% of the daily EONIA volume was reported by the five largest non-zero contributors according to the “Report by the working group on the euro risk-free rates on the transition from EONIA to ESTER” issued in December 2018.

[9] Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2016 on indices used as benchmarks in financial instruments and financial contracts or to measure the performance of investment funds.

[10] The €STR was published for the first time in October 2019. Between October 2019 and its discontinuation in January 2022, EONIA was calculated as the €STR plus a 8.5 basis points spread. (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2019/html/ecb.pr190531~a3788de8f8.en.html).

[11] Between 1 October 2019 and 22 November 2024, the average spread (in absolute terms) between the deposit facility rate and €STR was approx. 7.6 basis points. Over the same period, the 25th and the 75th percentile of the spread between €STR and the DFR stood at 6.1 and 9.4 bps, respectively. The spread widened temporarily from early 2020 to 2023H1, but more lately reconverged towards levels close to 8.5 bps. The €STR Annual Methodology Review published in December 2023 – covering the period from the beginning of October 2022 to the end of September 2023 during which the Governing Council raised the key ECB interest rates eight times by a cumulative by 325 bps – assessed that the €STR showed a full and immediate pass-through of the policy rate changes (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/financial_markets_and_interest_rates/euro_short-term_rate/html/ecb.eamr202312.en.html#toc4).

[12] The Eurosystem conducted partial reinvestments of redemptions under the APP from March 2023 to June 2023.

[13] As financial markets, institutions and counterparties adapt to changes in the liquidity environment alongside the reduction of the Eurosystem balance sheet, when concluding its review of the operational framework in March 2024, the Governing Council also communicated that it would carefully monitor the evolution and distribution of excess liquidity, the formation of money market rates, the evolution of banks’ demand for reserves, and the functioning of money markets and broader financial markets within the parameters announced (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2024/html/ecb.pr240313~807e240020.en.html).